A few weeks after my relocation to Muscat, I happened to read a controversial and now almost discredited book called The Passing of the Great Race. It was written by Madison Grant, an influential American lawyer, conservationist and eugenicist of the early 20th century. Madison Grant was an adviser to President Franklin Roosevelt and was an advocate of the immigration restriction law in the United States.The book propounds the supposed racial basis of the American “way of life”. It takes a detour from the anthropological history of Europe to what is described as the “Nordic theory” of race.

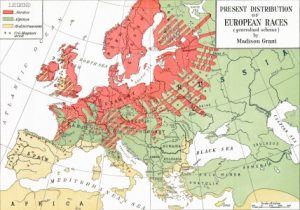

Nordicism, according to The Passing, states that Caucasians are not all identical as a race, but has three subgroups – the Nordics residing in Northern Europe, mainly the Danes, the Germans and the English; the Mediterraneans belonging to the southern Europe – the Italians, the Greeks etc; and the Alpines- residing in East Europe and Central Asia – the Slavs, the Turks etc. According to Nordicism, the Nordics are the master race, and responsible for much of modern civilisation.

The Nordic theory was quite popular in the United States in the early 20th century and was the ideological basis of the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921 which placed controls on immigration from South and East Europe and prohibited the immigration of Indians, East Asians and Arabs. The underlying belief was that the United States, and the American way of life is fundamentally a construct of the Northern Europeans and the immigration of other racial groups threatened its continuance.

This racial theory went into disrepute after the Nazis propagated it as their ideological basis. After World War II, with everything associated with Nazism bearing a stamp of “evil” and political incorrectness, the theory lost its popularity in American political circles. In the post world war era as the Soviet Union and the United States emerged as significant regional influences around the globe, the immigration restriction law based on “racists quotas” was a major embarrassment to the United States government. It was finally repealed and replaced by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. The latter considered skills of the immigration aspirants rather than their racial origin (indeed, the United States became truly the “land of freedom” only after the Immigration Restriction law was repealed. Until then the United States’ definition of freedom was devised and restricted to the “White Nordic race”. It was only fortuitous that the post-world war political environment developed an allergic antipathy to all Nazi signposts and Nordicism was submerged in the diplomatic overdrive for political correctness.

But is Nordicism completely baseless as my instincts for civil “correctness” insists it is? Can the whole history of western domination of the world be explained by any simple calculus of historical coincidences and first-mover advantages?

I seriously doubt my earlier convictions on this after learning the history of western intervention in West Asia. The context was my relocation to Oman for a 2-year job contract. The move to Muscat in a sweltering summer when the mercury soared to 51 degree Celsius, became key to my reimagination of world politics. Madison Grant’s The Passage of the Great Race was just a canvas on which I recast my political views.

Oman and West Asia as West’s Strategic Masterstroke

Oman was an underdeveloped country in the 1970s when its present ruler Sultan Qaboos bin Said took over. The country had only ten kilometres of motorable road, two primary schools and two hospitals for a country of three lakh square kilometres.

Sultan Qaboos did not take over as a natural successor. He dethroned his father Said bin Taimur in a bloodless palace coup. Bin Taimur was a conservative king heading a much improved nation in the 1960s when it faced insurgency in the southern province of Dhofar from rebels supported by the leftist government in neighbouring Yemen. He took a confrontational stance with the rebels and the government soon started losing ground with its people. Despite the oil resources, the Sultan was not interested in developing his nation and the rebels had the backing of the communist governments of China and the Soviet Union.

Qaboos bin Said was the second son of Said Taimur. He had his early education in India and later in England. He was trained in the Royal British Army. Returning to Oman, however, Qaboos was given a very limited role in governance, and was almost under house arrest in his palace at Salalah. In 1965, during one of the several periods of unrest in Oman, Said Taimur survived an assassination attempt. Since then he turned almost paranoid about his security and put the whole of Oman under his dictatorial watch, with very little civil liberty allowed. He saw modernisation as inherently evil and shut all avenues of modern influence in his nation. The population lived in utter ignorance and was divided along tribal lines. Their grievances were not addressed, and rebellions were suppressed on ad hoc basis with frequent help from the Royal British Army, with whom he had a military alliance . However, as the communist-abetted rebellion began in Dhofar, the British started feeling differently. They found the Sultan’s temperament incapable of providing a sustainable solution to his increasingly rebellious citizens. They found a suitable successor in his son Qaboos. Thus, aided by the very British officers he employed, Said Taimur was overthrown by his own son. Bin Said was sent to England, where he died in 1972.

Quite in line with their expectations, Qaboos was an able administrator. Unlike his father, he opened Oman to modernisation. Under the guidance of the British Army, the Dhofar rebellion was quelled with the deft use of the carrot and stick policy. The Sultan gave broad amnesty to rebellion leaders and many of the rebels were accommodated in various positions in the army and the government. As the Dhofar rebellion was suppressed, one of the most formidable incursions of leftist politics into the middle east soil was effectively neutralised. Thereafter, Oman was developed as a modern welfare under the tutelage of the British and US military and civilian planners. Most of the civilian and military institutions had western experts in leadership roles.The Sultan himself was very clear on how to utilise his power.

Driven from the oil revenue and western expertise, he invested heavily in education and the health of his citizens. The result was stupendous. Within a period of 30 years, Oman emerged from an impoverished state to one of the most peaceful and economically advanced states in the trouble-ridden West Asian region. While other nations were drawn to regional conflicts, Oman kept steadfastly neutral and maintained cordial relationships even between entities engaged in perpetual hostilities. This well-considered neutrality allowed Oman to develop as an oasis of stability in the general environment of internecine feuds prevalent in West Asia.

Successfully averting communist incursion into the West Asian oil treasure houses was indeed a master stroke of western strategic thinking. While in Oman this involved engineering a coup in favour of a leader groomed in the West, elsewhere in West Asia they employed the infamous “hand of God” to crush communist proclivities. The classical example of this strategy was in Saudi Arabia, where an ultra-conservative monarchy combined with mediaeval ideas of jurisprudence was cultivated to rule a land with one of the largest reserves of oil in the world. The Saudi family, in turn, promoted Muslim religious fundamentalism across the globe. Saudi-mentored Muslim religious conservatism proved to be effective antidotes against the development of ideas of proletariat liberation in the all of the Islamic world. This was, perhaps, the most economical solution against liberation theories propounded by the leftist movements.

Unlike the present persona of the West as a champion of democracy, human rights and liberty, the West’s record of fairness in the immediate post-war world was quite dismal. The fountainhead of capitalism, the United States was, as we saw before, was essentially a free world only for the “Nordic Caucasians”. Until the 1950s there was nothing in the records of the Western world that could have enamoured the common population of the newly decolonized nations to embrace the West as their trustworthy ally. Therefore, the policy of the West was to carry out their channel of influence through dictators, monarchs and authoritarian leaders. While this was successful to a variable extent in various parts of the world, in West Asia this strategy was uniformly successful.

The West played its strategy in West Asia so well that all the states that were allies of the West, fared well in the subsequent decades. Such western protectorates include Bahrain, Qatar, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Oman. On the other hand, after the fall of the Soviet Union, all those states in West Asia who were independent or allies of the Soviets were systematically destabilised. This includes Iraq, Libya, Syria, Lebanon, Algeria, Egypt, and Yemen. The only exception is Iran, which we know, is a contemporary project in action. Even during the recent Arab Spring turmoil, while in states like Egypt, Libya and Tunisia there were dramatic changes in the regime, the protests in a steadfast ally of the West like Bahrain easily fizzled out. All those states that remain in the western sphere of influence stayed stable throughout the period of turmoil.

One such western protectorate that has enjoyed prolonged stability in West Asia is Jordan. Jordan is ruled by the Hashemite Kingdom. The Hashemite Kingdom was virtually “founded” by the British to rule over the present-day territory of Iraq, Jordan and Syria. The British handpicked the Hashemite family because it is believed that the family originated from Hashim Manaf, the bloodline of Prophet Muhammad. After breaking the Turkish Ottoman Empire, the British in their strategic wisdom thought that the bloodline of the Prophet would make the kind of royal family that would appear legitimate to the Arabian tribes, and would serve the British interest in the region well. The British looked at the nature of tribal loyalties in Arabia and “installed” kingdoms that would be respected along tribal lines. I think such an exercise is unprecedented in the history of the modern world.

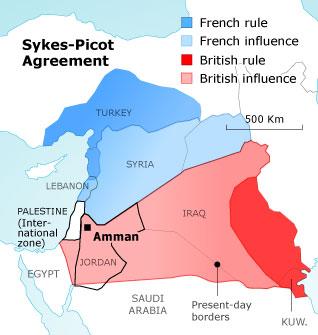

Sykes-Picot was a secret pact for division of West Asia by the Imperial European forces among themselves. The existence of the pact was disclosed by the Bolsheviks after the Russian revolution. The agreement was to divide West Asia to zones of influence and occupation after the planned destruction of the Ottoman Empire. Sykes-Picot is the first of a series of intervention of the Western forces in the West Asia that had long lasting influence in the region

The original British colonial interest in the Middle-East, when they secured a military alliance with the ruler of Oman, was to secure their trade route to India. Colonising the Middle-East was not an economically meaningful proposition. However, the discovery of oil in West Asia changed everything. Between 1911 when oil was discovered in Iran and the 1970s when the oil industry was almost handed over to the Arab states, the British, Dutch and American oil companies systematically explored and uncovered commercially viable reserves of oil in West Asia. But for the initiative, futuristic thinking and the perseverance of these companies, West Asia would have remained a desolate land of nomadic tribes. The prosperity of the Middle East, was in every sense, delivered and quickened by the exploratory spirit of the Western companies. Tactically, it was natural that they strived to preserve the fruits of their efforts slipping to the hands of their ideological enemies.

West Asia and South Asia

The ultimate effect of the western intervention in West Asia was to stabilise the states that provided unwavering support to Western interests, and destabilise those who deviated from this fundamental agenda. Thus, attempts of various alternative political formations like independent nationalists or pan-Arab socialist movements were dislodged over a period of time. Many of these nations had strong popular leaders at one time or another, and used “quasi-democratic” processes to get themselves elected. The list includes Nasser Gabel in Egypt, Hafez al-Assad in Syria and Saddam Hussain in Iraq. They provided robust leadership to their countries and appropriated space between the communist and capitalist blocks.

Gabel championed the Non-Aligned movement, Assad devastated fundamentalist upshots in Syria, and Saddam Husaain presided over a nation that had the fastest growth in the 1970s among the West Asian nations. All these states evolved as broadly secular nations, and were kept out of bounds to the fundamentalist sectarian movements. However, all these nations were embroiled in violent conflicts internally and externally, and tried to negotiate conflicts with authoritarian policies that sidelined any opposition in very undemocratic ways. None of these leaders could establish strong democratic institutions, and their authoritarian tendencies and politics of hostility generated opportunities for their adversaries to sneak in.

If you run a counterfactual analysis of this narrative, the significance of the western intervention in West Asia would be evident. If the western checkmate of communist incursion through Yemen was not checked, none of these prosperous West Asian economies would have emerged. Indeed, all those West Asian states that ejected out monarchies or West-inspired kingdoms degenerated into illiberal democracies or autocracies. Egypt, Iraq, Iran and Syria are examples.

Regions in South Asia like my native state Kerala prospered when its population found employment during the nation building of middle-eastern nations that were stabilised by western forces. UAE and Oman were virtually built from scratch by the labour and technical inputs from the Keralite population. Similarly, there is significant contribution of Pakistani and Bangladeshi labourers in the development of Saudi Arabia.

In short, the action of the West in the West Asian theatre was so long-sighted that it changed the destiny of regions as far as South Asia. This says a lot about the strategic insights of the Western forces in the early and mid-20th century.

I am not sure this has anything to do with “master race” theory, but the western thinking about the future is definitely more profound than all other nations put together. Perhaps, it has nothing to do with a genetic idea of race, but it clearly has something to do with how cultures evolved in these nations. The question left unanswered is whether cultures are different in some strange ways that are fundamental to their existence. I shall examine this question in a different light when we examine the nature of Jewish identity.

Footnotes

- The Muslim Ottoman Empire of Turkey was one of the largest and longest of all Empires. It extended from 13th century to early 20th century, from the outskirts of Vienna in the West to Azerbaijan in the East. It had trade monopoly through land and its military and navy was the largest its contemporary world had ever seen. British under the leadership of Thomas Edward Lawrence was able to break the mighty Ottoman Empire and allow the Arab insurgents to gain power

- An interesting comparison is the ability of Indian founding leaders under Nehru to nurture democratic institution in a nation as complex and diverse as India, while many of the similarly or less diverse nations was degenerated as authoritarian regimes.

- I consider counterfactual analysis as an important tool in historiography to illustrate the importance of historical facts. I shall discuss it in detail in relation with appropriate examples.

Hits: 22325