One of the things I was fascinated by during adolescence and early adulthood was the rapid rise of fortunes in the Western world which began in the 17th-18th centuries. We learn from our History and Civics textbooks that this rise to fortune was incidental to the development of science and technology and the subsequent European colonisation. But the big question that lingered was why science and technology did not develop in India and other older civilisations the way it flourished in the West.

In the late 1990s, just after my final MBBS examination, I scouted libraries in my hometown, Calicut, for answers. It was the pre-Wikipedia era and answers were not really forthcoming. I browsed through multiple reference books in our central library, and finally got a reasonable answer from the volumes of the Encyclopaedia Britannica-the story of European Renaissance.

Renaissance is literally translated as “rebirth”. The story is that Europe plunged into a dark period in the Middle Ages from the 5th to 15th centuries, when the Church dominated Europe. It was during Renaissance that Europe rediscovered the ethos of Ancient Greece and Rome. A sequence of events thereafter led to the development of major cultural and political changes, including the rapid development of science and technology, the fruits of which gave the European powers the motivation and edge for global exploration and colonisation.

.

In other words, Renaissance was sort of a “rupture” that set in course events that led to the divergence in the fortunes of the West from the “rest” of the world.

I have seen this narrative recanted in many popular science portals and history books. The word is used liberally in multiple other contexts. We see the word “Renaissance” used for the cultural awakening in Bengal in the early 20th century. The state of Oman has a “Renaissance Day ”, which marks the coming of power of the reformer Sultan, Qaboos bin Said. Kerala’s social reformation in the late 19th and early 20th century is sometimes called a “Renaissance”. It is obvious that all these adaptations come from the coinage of the term in Europe. But are they all the same? Is the widespread adaptation of this term for all sorts of social reform movements conceptually correct?

British-American right-wing historian Niall Ferguson discussed the nuances of this “divergence” in greater detail in his book “Civilization: The West and the Rest”. I have written an annotated review of the book by rereading the book and weeding out the biases that come from his disposition as an American imperialist. Stripped of his biases though, the book is a decent documentation of the operating forces that affected the divergence which shaped the political, cultural and economic landscape of the world we currently live in. So when I visited Rome in March 2022, I took a necessary detour to take a closer look at the birthplace of European Renaissance that was the stuff of legends.

Florence is a small city in Italy, but its importance in the history of the western world far exceeds its size.

It is considered the cradle of the European Renaissance. Historians who coined the term, consider the period an era of rediscovery.This implies that what preceded this era was the “Middle-Ages” that were dark and stagnant. Renaissance apologists called this period the “Dark Ages”.

At the time, Medici, a family in Florence that made a fortune by trading in wool and later in banking, gained prominence in public affairs. The head of the family, Ardingo de’ Medici became the Gonfalonier( a post equivalent to that of civic magistrate). The Medici family dominated the financial and political landscape of the city-state for the next three hundred years. Among many others, the Medici bank is credited with the development of the double-entry bookkeeping system that made large-scale bank accounting seamless.2 Medici had a special relation with the Pope and handled the finances of the church. They also lent money to many warring European nations. At its zenith, the Medici family was the wealthiest in all of Europe. The family engaged in conjugal relationships with many ruling families in Europe, and by 1531 transformed the republic into a monarchy by establishing the Dukedom of the Florentine Republic.1

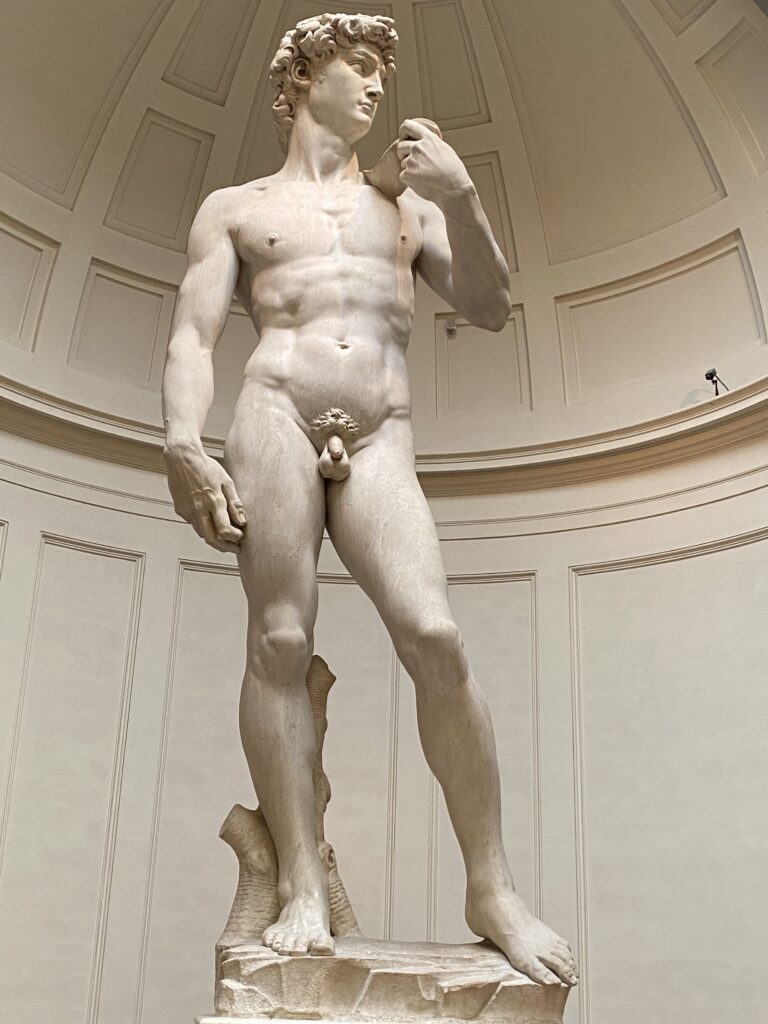

In the early stages of the Florentine republic, it was customary for business houses to fund public services for prestige and privilege. The Medici family was prolific in this regard. They funded numerous artists and craftsmen, and constructed an array of landmark buildings. The signature dome in Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore was engineered by Filippo Brunelleschi, a goldsmith by profession, who designed the dome by studying ancient Roman architecture. The interior of the dome was frescoed by Giorgio Vasari and Federico Zuccari. The Medicis financed Michelangelo, Leonardo Da Vinci and Raphael who defined the European art of that era and beyond.

In 1453, Constantinople (present day Istanbul), the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire fell to the Ottoman Turk invasion. This was the culmination of a campaign that spanned decades. The Eastern Roman Empire, also called the Byzantine Empire, was not in talking terms with the Italian kingdoms because of a theological dispute dating back to the 11th century. The main language of the Italian kingdoms was Latin, while the Eastern Roman Empire had preserved Greek as the language of scholarly communication. The conflict between the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Roman Empire almost created a scholarly embargo on many ancient Greek texts preserved in the Byzantine Empire. The threat of Ottoman invasions and the eventual fall of Constantinople led to an exodus of scholars of ancient Greek from the Eastern Roman Empire. Many of these scholars settled in Florence and were patronised by the Medici family. Prior to this, Lorenzo de’ Medici had commissioned a delegation to “oriental” countries to collect Greek manuscripts. The Medici family also invested in collecting scientific and measuring equipment from across Europe and the “Orient”.

In 1657, Leopoldo de’ Medici, the brother of Ferdinando II de’ Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, founded the “Academy del Cimento” to pursue his interest in natural philosophy. The motto of the academy was “Provando e riprovando” (by testing and retesting) with an emphatic focus on performing scientific experiments. This was one of the first dedicated scientific societies in Europe. The members of the society studied a wide range of subjects, from astronomy and mathematics and development of measuring equipment like barometer and thermometer, to anatomy. Another event of great importance took place during this time: Medici extended an invitation to Galileo Galilei to move to Florence and provided patronage throughout his tumultuous career.

In the 12th century, as the Arabs who had occupied Europe were pushed back, there was a flurry of Latin translations of the Arabic version of ancient Greek works, especially those of logic, mathematics and natural philosophy. These Latin texts were used in early European universities to develop a curriculum on theology, philosophy and mathematics. Biblical stories were admixed with Ancient Greek philosophy, and a body of literature was developed for University education. The bedrock of Christian theology was the Latinised texts of Greek philosopher Aristotle. Formal education was centred on the study of various interpretations of an amalgamation of Aristotelian philosophy and Christian theology. The highest form of education in the Universities of the Middle Ages was studying theology. Most intellectual exercises in the Universities were simply the interpretation and reinterpretation of Latinised theological and philosophical texts that were in currency. This kind of curriculum practiced in the medieval universities of Europe was roughly dubbed as “Scholasticism”.

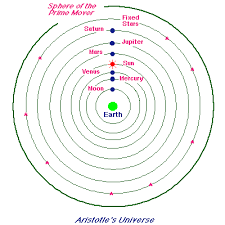

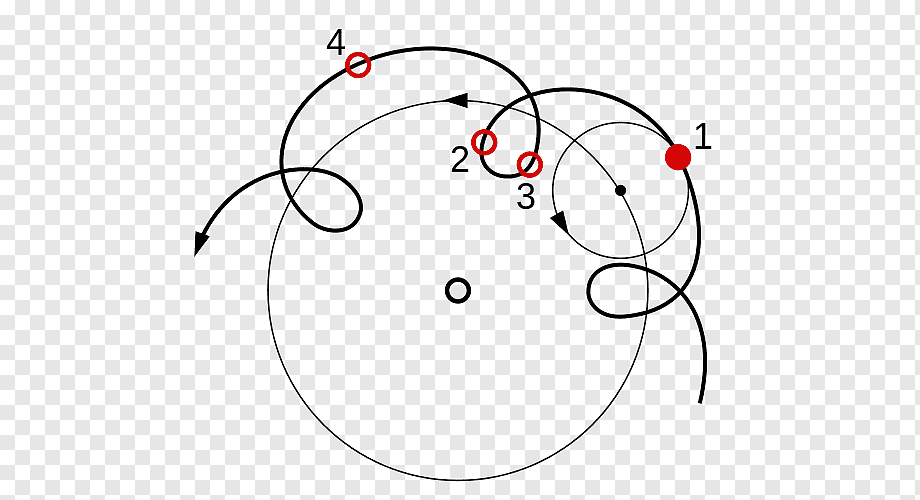

Aristotle’s worldview was indeed only a common-sense interpretation of universal phenomena – like proclaiming that the universe was spherical and centred on a static earth. He made other similar observations: planets and stars were stuck in onion- layered spheres orbiting the earth (figure);bodies fall to the earth because earth is the centre of the universe; heavy objects fall faster than lighter objects, and heavenly bodies- planets and stars- behave different from the objects below the moon (named as sublunar objects) because of the “inherent” tendency of heavenly objects (supralunar objects) to spin around, in various layers of the heavens.

After the Ottoman Turk conquest of Constantinople, Italian scholars became increasingly exposed to the original Ancient Greek texts. Independent scholars who examined these texts found errors and additions in the Latin translation taught in Universities. They found Ancient Greek works “human-centric” and mostly devoid of the supernatural fanfare of the Latin versions that were available in the university curriculum. Many works like that of Plato, Pythagoras and Protagoras were discovered anew. Pythagorean mathematics enhanced the status of mathematics as a discipline. Protagoras’ slogan, “Man is the measure of all things” – a dictum popularised later in the European Enlightenment movement- was initially scorned by his contemporaries as an argument for “relativism”. Interests in the works of antiquity also kindled engineering projects inspired by the ancient construction in Rome and Greece.

The “humanism” that emerged in the Renaissance era should not be confused with the “secular humanism” of the 19th and 20th centuries that demanded separation of the Church and the State.3 The word “humanism” of the Renaissance era is actually a corruption of the word “humanists”. It just meant a group of scholars interested in the study of humanities (mainly grammar, history, poetry and philosophy of Ancient Greece and Rome). The Jesuits scholars were deeply involved in the process. Many Popes who reigned during the period were themselves considered humanists. They commissioned massive art works that depicted the newfound fascination with ancient humanities. This exposure to the pagan philosophies of Greece made visible changes in the Scholasticism prevalent until then.

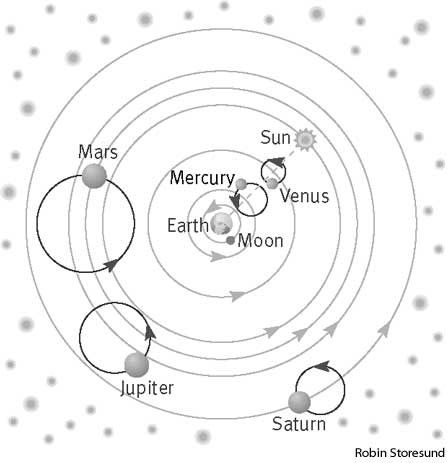

In 1514 Nicholas Copernicus, an administrator of a Church in present-day Poland, came up with a model which had the sun in the centre, and the earth rotating on its axis, revolving around the sun. This elegantly explained the issue of retrograde motion of planets (see Figure below). The Copernicus model was also much simpler than the complicated Ptolemy model that made several subsidiary assumptions to Aristotle’s geocentric one (see Figure above). Although it was circulated as a manuscript, Copernicus was wary of publishing it, probably because of his apprehension about the Church’s response on the matter (it contradicted the Biblical passage that the earth was essentially static).

When the Copernicus model was presented to Pope Clement VII and his cardinals by one of the Pope’s officials, it prompted the Cardinal of Capua, Nicholas Schonberg, to write to Copernicus asking him to publish it as a book. Hesitant still, Copernicus chose to publish the model only towards the end of his lifetime. The book, On Revolutions of Heavenly Orbs, was available in print only after Copernicus’ death. But the book did not stir major controversies because the scholar who wrote its foreword – a clergyman named Andreas Osiander- presented it as a hypothesis. The Church thought that it would remain a hypothesis that is unlikely to be verified. Indeed, there were no known methods to verify what Copernicus postulated about the nature of the earth and the heavens. It remained an unverified hypothesis until our next character emerged.

Galelio Galilei, joined as a professor of Mathematics in the University of Padua roughly fifty years after Copernicus published his book on the heliocentric model. Although Galileo was acquainted with the Copernican model, he did not consider teaching it in his university course.

In 1608, the telescope was invented in the Netherlands. Galileo worked on the device and improved it enough for it to be used in making astronomical observations. His observations of the heavenly bodies provided him with the necessary proof to revisit the Copernican model. Galileo found that the moon’s surface is similar to that of the earth – with mountains and valleys; that Jupiter has four moons orbiting it; and Venus has phases like that of the Moon. The phases of Venus virtually disproved Ptolemy’s model of planets.4

In Ptolemy’s model, Venus was between the sun and the earth. Full and crescent Venus proves that it is sometimes between the sun and the earth, and sometimes on the far side of the sun, away from the Earth. If it was between the earth and the sun, as in a geocentric model, it would always be a crescent or lesser, but not a full Venus. Galileo also discovered the phenomenon of waxing and waning in the brightness and size of Mars, as was predicted by the Copernican model.

In 1610, Galileo published his discoveries in the book titled Starry Messenger. He dispatched copies of the book along with telescopes to rulers across Europe. The discoveries brought Galileo many endorsements, including followers from the Jesuit community. Eminent scholars in astronomy and mathematics wrote in his favour.3 Soon the geostatic theory of Aristotle and Ptolemy lost support with new evidence in hand.4 However, there was growing discontent against the geokinetic model from the theological community. There were few biblical passages that clearly stated that the Earth is static, and as far as the Church was concerned the biblical passages were sacrosanct.

As the debate on Starry Messenger was creating a stir in social circles, Galileo wrote a long letter addressing the issues concerning the alleged biblical objections of the Grand Duchess of Tuscany, mother of his patron, Cosimo II de Medici. The Duchess had raised the issue of scriptural objections to the geokinetic model to a friend of Galilio, Father Benedetto Castelli, at a dinner party she hosted. Castelli reported this incident to Galileo, and Galileo thought that it would be prudent to write a detailed letter to the Duchess explaining his position on the matter. In this letter Galileo argued, quoting many influential Christian theologians, that scriptures need not be interpreted literally, and that nature as revealed through observation should be given precedence over what is written in scriptural texts. He went on to state that “truly demonstrated physical observations” do not have to be modified in the light of the Bible, rather, the scripture needs to be reinterpreted in light of new evidence.6,7

This letter was circulated widely, and irked the traditionalists who thought it an arrogant affront to their theological authority. In 1614, a monk in Florence named Tommaso Caccini held a Sunday sermon against Galileo. Another monk, Niccolo Lorini, filed a complaint against Galileo with the Inquisition – the infamous office of the Catholic Church that was deputed with the task of investigating and punishing heresy. The Church constituted a committee, and in 1616 reported that Copernicanism was untenable and should be considered heresy. It directed Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, Galileo’s friend and an influential theologian, to deliver a private warning to Galileo against defending geokinetic views. The committee censored Copernicus’ book and other books supporting the Copernican model. Galileo apparently promised Cardinal Bellarmine that he would obey the Church’s dictates and the proceedings were wrapped up without publicly naming Galileo.4

Galileo maintained his promise for almost a decade. In 1623, a Florentine Cardinal named Maffeo Barberini was elected as Pope Urban VIII. Urban was an admirer of Galileo and in 1616, was instrumental in preventing the formal condemnation of the astronomer. Galileo dedicated his book on comets to the Pope which pleased him, and in 1624, Galileo was given an extended audience and stayed in Rome for a period of six weeks to meet with the Pope on a weekly basis. During these meetings, Galileo seems to have ascertained the Pope’s opinion on the scope of the 1616 decree on the Copernican model. It appeared to Galileo that the Pope was of the opinion that a hypothetical discussion of Copernicanism was harmless.

After his meeting with the Pope at Rome, Galileo started work on his next book. He wrote the book as a dialogue between three people – one, representing Copernican position, another, representing the traditional geostatic view, and the third person presenting themselves as an educated spectator. The book titled Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, Ptolemaic and Copernican, was published in Florence with a dedication to Galileo’s Medici sponsor, the Grand Duke of Tuscany.5

Although the book was well received in the scholarly circles, complaints started to pour from the religious circles. The main issue was that the tone of the book, although written as an equivocal dialogue between two sides, sided with establishing the Copernican system. In fact, the character who advanced the side of the geostatic model was called Simplicio, which many believed was a double entendre for “simpleton”. Critics said that the whole purpose of the exercise was to ridicule traditional viewpoints.

The Pope who was embroiled in major political and religious upheavals with The Thirty Years’ War and the Protestant Reformist Movement did not take the case lightly. After a commission of inquiry, the case was referred to the notorious body of Inquisition. Despite much maneuvering by the Tuscany government, Galileo was given an ultimatum by December 1632 to appear for the probe by January 1633. In June 1633, Galileo was found guilty of heresy, and was put under house arrest until his death in 1642 at the age of 77.

Medici continued to support Galileo even after the verdict of the Inquisition and Galileo pursued his experimental work during his house arrest. He completed his book, Two New Sciences during this period. This volume is considered his most important contribution. He established, by means of experiment, that all bodies fall at the same rate regardless of their weight. Galileo also deduced that while a ball rolled up a slope slows down and accelerates down the slope, a ball on a flat surface would theoretically move eternally unless acted upon by something. The principle of inertia was also put forth by him which explained the eternal motion of the planets around the sun as a fundamental property of constant motion. Here, Galileo thwarted the need for a separate explanation of the almost perpetual motion of the heavenly objects in Aristotle’s model of the universe. This marked the dawn of the modern principles of mechanics.

Significantly, he started to use mathematics in the study of motion – an application that would revolutionise the subject-matter of physics in the centuries to come. Here, Galileo expanded the techniques used by an Italian engineer Niccolo Tartaglia (1499-1557). Tartaglia was the first to use mathematics to study the projectiles of canon balls. He translated the works of Archimedes and Euclid to Italian, and applied Euclidean geometry to predict the trajectory of projectiles, building the basics of ballistics that is used in military sciences. Galileo adapted the methodology of Tartaglia in the study of falling bodies.3

Galileo’s concept of inertia and the constant motion of objects was advanced by Newton after Galileo’s death. Newton synthesised his idea of gravity upon “magnetism”- like forces acting at a distance, a theory postulated by Johannes Kepler, another 16th century astronomer-mathematician. Soon, mathematical reasoning in physics would assume a life of its own. This remains the singular most important phenomenon that revolutionised the methods of science.

In Florence, there is a museum commemorating Galileo called Museo Galileo. The museum’s manual claims that the collection of scientific instruments preserved in it is one of the most important in the world.8 It exhibits the scientific equipment collected by the Medici family and the Lorraine family who ruled Florence. Unfortunately it is one of the most low profile museums in Florence. It is barely mentioned in any travel recommendation lists to Florence and does not make it to the itinerary of most guided tours. I discovered the museum from a tour advertised in the New Scientist magazine many years ago. This tour titled the “Science of Renaissance” features Florence as the key centre of Renaissance Science. Two of the three science museums mentioned in the tour are closed down, making Museo Galileo the saving grace in preserving the science of the Renaissance.

To conclude, Renaissance-era Florence did not show an abrupt “rupture” from the Middle Ages as is widely claimed in popular literature. The agents of the Middle Ages, the Church, the Popes and the aristocracy were very much part of the proud exhibits of the Renaissance movement. What is indeed revolutionary, is the works of physicist-mathematicians like Galileo and Kepler who brought observational investigations of the physical world into a solid platform of mathematics as a means of theoretical reasoning. This slowly weaned away the habits of Scholasticism that had encroached Western Universities from the time they were established.

Discovery of ancient Greek ideas of philosophy on the importance of human agency and ancient Roman ideas of exercise of political power inspired political ideology on republicanism well into the future, finding its way to the American independence movement. Jefferson in fact, quoted Roman senator Cicero’s speech when he wrote the charter of American independence. Many American seats of power were inspired by Roman architecture. The Capitol, the seat of US Congress, is modelled after the Roman Pantheon. It is probable that the policies of the American statecraft that demonstrate strong tendencies of “exceptionalism” are modelled on the policies the Roman Empire used to wield power. Renaissance-era political theorist Niccolo Machiavelli used examples from Ancient Rome, of duplicitous exercise of power as the model by which rulers should work to preserve the integrity of the monarchy or the Republic. Machiavelli’s political philosophy bears close resemblance to the practice of politics in America.

Renaissance in many ways was a mixed bag. Its steady transition lasted hundreds of years during which the Europeans started discovering ideas which they had not been exposed to during the Middle Ages. For the non-Europeans it’s an important transition period as it serves to connect the dotted lines in their cultural history by understanding what was missing before modernity was imported by Europeans as a colonial buy-one-get-two package.

Acknowledgment: I would like to thank Drs Sasikumar Kurup, Sabish Balan and Dhanya Jayaraj for their inputs on this entry. Our visit to Museo Galileo would have been futile without the curation of Martina whom we met at the last minute. Martina helped us understand the provenance and the historicity of equipment displaced in the museum.

References

1. Hibbert C. The Medici : the rise and fall. New York: Morrow; 1975.

2. Ferguson N. The Ascent of Money. Penguin Books Ltd; 2012.

3. Principe L. The scientific revolution : a very short introduction. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011.

4. Finocchiaro MA, Galileo Galilei. The Galileo affair : a documentary history. Berkeley, Calif.: University Of California; 1989.

5. Galileo Galilei, Finocchiaro MA, Netlibrary I. Galileo on the world systems : a new abridged translation and guide. Berkeley: University Of California Press; 1997.

6.Galilei, Galileo. 1957. Letter to Madame Christina of Lorraine, Grand Duchess of Tuscany concerning the use of biblical quotations in maters of science (1615). Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo. 175-216.

7. Moss, Jean Dietz. 1983. Galileo’s Letter to Christina: Some Rhetorical Consideration. Renaissance Quarterly. 36: 547-576.

8. Camerota, Filippo. 2010. Museo Galileo: masterpieces of science. Firenze: Giunti.

Hits: 695