British historian Niall Ferguson’s book Civilization: The West and the Rest ( Alien Lane, Penguin Group, 2011) is an interesting survey of the history of the world over the last thousand years. It examines the rise of Western civilisation through many historical intersections that were crucial in outsmarting its rival formations.

I would recommend this book as a must-read for anyone interested in politics, science, or technology, as it provides a synopsis of the West vis-à-vis the ‘rest’ across the grand scale of a millennium. It also helps us reevaluate what we learned during our school years as historical facts and see how much of it was fabricated, and how much continues to be fed to us through the many superfluous debates that inhabit our pop media.

Another important reason why this book is a must-read is that it enables us to reflect upon the strategies of the Japanese (from the late 19th century to the early 20th century) and the Chinese (from the late 20th century onwards), adapted in replicating the advances of the West. It could provide insight into a window of strategies that India as a nation ought to adapt, to replicate what the Japanese achieved and what the Chinese aim to achieve.

Being a monumental survey of world history through a one-thousand-year timeline, the arguments are not straightforward. Many tangential subtexts intersect the mainstream flow of the argument. To separate the author’s position from my commentary on the context, and to provide a critique of the author’s narrative, I have used italicised text wherever appropriate.

As a general issue in approaching works in humanities, authors quite often get carried away by their own theories and predilections. This pertains partly to the lack of a rigorous logical tool to crop and restrain arguments (the kind of mathematical restrain available in exact sciences like physics) and partly because of the very nature of the subject (of the innate complexity that does not allow mathematical reduction and the consequent qualitative nature of interpretation). Ferguson’s arguments are not absent of such biases either. Despite this, I feel that a significant part of his arguments would withstand scrutiny.

Four ‘Killer Applications’

According to Ferguson, the crucial difference between the West and the “rest” is institutional. Using the lingo of the smart-phone age, Ferguson stitches the narrative of Western ascent using what he describes as the six “killer applications”, which the West identified and fostered over the course of time – vis: trade, science, medicine, work ethics, property rights, and democracy (based on rights of ownership) and consumerism that sustained market-driven mass production and industrialisation.

Ferguson considers these properties as “differentials” around which the West diverged from other civilisations/cultures that may have possessed some of the same “properties”.

He explains these “institutional differences” in six spheres of activity:

Competition ( or trade) – how the West diverged from ancient China

Science (the way of studying, understanding and ultimately changing the natural world) – how the West diverged from the Muslim Ottoman Empire.

Property rights(and the rule of law based on private property rights) – how they formed the basis of a stable form of democratic governance as seen in the United States.

Medicine( “the branch of science that allowed improvement in health and life expectancy”) – the divergence from the “Rest” as a whole.

Consumer society(the consumer being the central operating principle of the economy and the industry – as opposed to the whim of the central planners who impose “desires and limits of desire” on people) – the divergence and eventual western outsmarting of the 20th century Soviet “empire”.

Work ethics (the frugality and work-worship in Protestant Christianity) – the divergence of the Anglo-Saxon nations from the rest of the world, in forming the core of the West.

West

Here, the term “west” is not entirely geographical, it is a set of norms, behaviours, and institutions without borders. Accordingly, there are different propositions to the delimitations of the West. Ferguson sympathises with the description of the US historian Samuel Huntington (of The Clash of Civilizations fame) which includes Western and Central Europe, North America, and Australasia. It excludes Mediterranean nations like Greece (even though ancient Greece is considered the fountainhead of Western thought) and Cyprus and eastern European countries like Serbia and Russia.

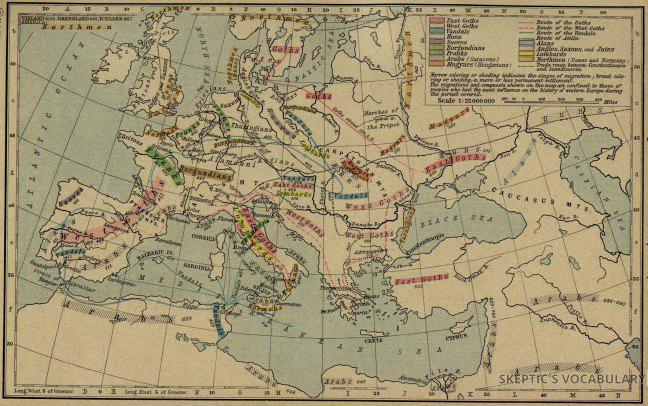

1) The First Front: Trade – Divergence from Ancient China

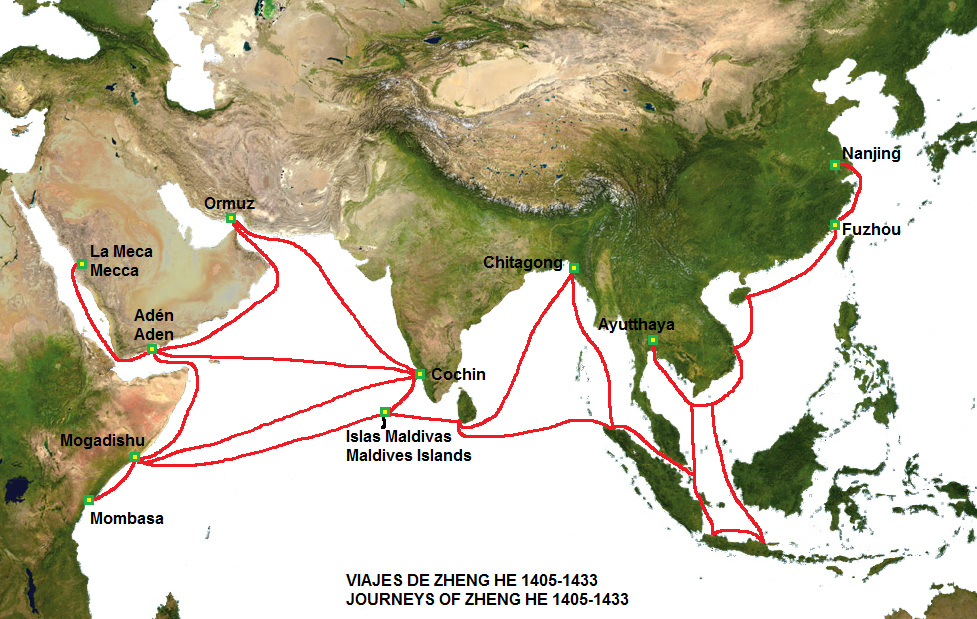

China in the first half of the 1000s was more sophisticated than the rest of the world, displaying prescient signs of a major industrial revolution. The water clock, paper, printing press, mechanised textile instruments, and gunpowder were all Chinese innovations. Chinese Admiral Zheng He traveled across the Indian Ocean, in a ship five times the size of Vasco da Gama’s Santa Maria, years before Da Gama made his voyage. The Chinese navy with a combined crew of 28,000 was bigger than any Western navy until the First World War. However, Zheng He’s voyage was quite unlike that of Da Gama.

He didn’t want to engage in trade, but go to the barbarian countries and confer presents on them to transform them by “displaying our power”. On one of his voyages, he reached the east coast of Africa, only to bring home a giraffe presented to him by the Sultan of Malindi! By contrast, Vasco da Gama’s brief was “to make discoveries and go in search of spices”. Chinese confidence in their self-sufficiency and superiority was such, that when Earl Macartney led an expedition in 1793 with the hope of persuading the Chinese to open their empire to trade with an assortment of items like telescopes, air pumps, and electrical machines, the Chinese Emperor wrote a dismissive edit to the English King stating “we have never set much store on strange or ingenious objects, nor do we need any more of your country’s manufactures”.

Ferguson says that it is this Chinese antipathy for trade with the world that retarded China’s progress and accelerated Europe’s, despite having a head-start in science and technology.

However, the 21st-century Chinese rulers seem to have realised this mistake and are making amends. Presently, the Chinese trade with anyone who they think are good enough to trade with – whether it is African despots or Burmese generals – irrespective of what ideological poles they are at. Ferguson quotes Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping articulating this position,“No country that wishes to become developed can pursue closed-door policies. We have tested this bitter experience – 300 years of isolation has made China poor, backward, and mired in darkness and ignorance. No, open-door is not an option.”

2) The Second Front: Technology from Science- Divergence from the Islamic Ottoman Empire

The Muslim Ottoman Empire of Turkey was one of the largest and longest-serving Empires, from the 13 CE to early 20 CE, with territories extending from the outskirts of Vienna in the West to Azerbaijan in the East. It had a trade monopoly through land, and its military and navy were better than anything the contemporary world has seen. When Europe was reeling in the “Dark Ages”, it was the Ottoman Turks who preserved the ancient Greek ideas (which would later form the fountainhead of the European renaissance). They had adapted the best of the Indian school of mathematics and even made seminal contributions.

Ottoman lost to the West in the development and adaptation of science and technology

However, a “great divergence” developed in the 16th century when Europe was progressing to the next stage of its development: Renaissance (literally the “rebirth” of what many believe was the Greek school of thought). It was the period when the stranglehold of the Church was weakening, and Europe began thinking of a world beyond biblical scriptures. During the period between the 1500s and 1700s, twenty nine major breakthroughs happened “in a hexagon bounded by Glasgow, Copenhagen, Naples, Marseille, and Plymouth.” These key discoveries ranged from the work of Paracelsus ( physiology and pathology), Copernicus ( astronomy), Galileo (mechanics), Hooke (microscopy), Lippershey, and Jansen (telescope), to name a few.

On the other hand, this was the time when the Islamic clergy was tightening their grip over the Ottoman Empire. What was vogue in medieval Europe was becoming vogue in the (European) renaissance-era of the Ottoman Empire. Printing was resisted in the Muslim world, as the “scholar’s ink” was thought to be “holier than the martyr’s blood”. Soon after, a royal decree threatened anyone found using the printing press with death. Ferguson says that Muslim scientists, thus, became effectively “offline”, cut off from the scientific development in Europe.

The intellectual advances in Europe were then transmuted into military advances. In 1742, Benjamin Robbins published a volume on the New Principles of Gunnery based on the principles of physics and mathematics (especially calculus) developed by Newton. This then translated to better artillery designs that in no time outsmarted the ancient cannons of the Turks.

Ferguson sees this as the second front of the Western “ascent”.

3) The Third Front: Private Property and Democracy- Divergence from Colonial South America

The third “differential” operated between North and South America. While North America developed as the vanguard of the Western civilisation, South America remained a laggard as one among the “The Third World”. Ferguson sees this as the result of the development of private ownership and democratic representation based on property ownership.

The Spanish and Portuguese who colonised Southern Africa didn’t have the disadvantages of the Chinese or the Ottoman Empire. They were pioneers who conquered the sea routes, and were exposed to the scientific revolution of the post-renaissance era. Yet, the Southern states lagged behind North America.

The Spanish who colonised the South started with cheap gold and silver that was available in South America, initially plundering the Inca resources, and later establishing their mines. The colony was managed by a tiny group of Spaniards using indigenous labor, while the land itself was owned by the Spanish Crown. In the North, which was mainly colonised by the British, however, the situation was quite different. According to Ferguson, North America didn’t have the ready-made resources of the South. What was in plenty were enormous tracts of land.

The British colonisation of America coincided with a scenario that would have incited a Malthusian Population Trap (after Thomas Malthus who stated that natural resources are limited and cannot keep up with the population explosion which will result in a breaking point in all closed communities) in the English isles. However, the Malthusian predictions didn’t happen, as there was “an exit option for those willing to risk a Trans-Atlantic voyage”.

Ferguson says that the “exported labor” was more productive in land-rich, labor-poor America. It also benefited those who stayed behind in Europe as it prevented the local wages in Europe from falling (as Malthus predicted), and soon resulted in a progressive increase in wages, because the exodus of labor to the Americas created a healthy balance between supply and demand of labor.

As land and its ownership became key in the initial stages of the North American economy, its protection against engorgement became the template of North American governance. The initial parliamentary system in Carolina where the first settlement started was based on “land ownership status”; the voting right was decided based on the ownership of a “minimum of 100 acres of land”. However, this did not mean that the voting right multiplied, those who had land dominated the scene, with each person owning a hundred to a thousand times the amount that made him eligible for voting (Picketty, 2021). For instance, when George Washington executed his will, his estate totalled 52194 acres of land. In the 1700s this was a revolutionary idea, as in those times, everywhere else a person’s “legal” ( as opposed to extralegal) power was proportional to “asset” power.

Ferguson says that the concept of “rule of law” developed – perhaps rather pragmatically – as a method to protect private land ownership. Ferguson seems to suggest that democracy developed and consolidated on this pragmatic goal, rather than on any high pedestal ideas of liberty and freedom.

I think this is an important point to understand. Democracy, as we see it today, is not immediately apparent as an ideal form of governance. In the Age of Monarchy, that was thought to be the ideal form of governance .

This not-so-idealistic development of the New World institutions becomes evident when Ferguson notes that one of the principal incentives for the American revolt against the British government was its opposition to further advancement of European settlements into the Native American heartland ( towards the west of the Appalachian Mountain range).

Ferguson maintains that property speculators like George Washington ( the same Washington who is one of the founding fathers of the USA) could not stomach this. They saw the land occupied by the indigenous tribes as a land of opportunity, which should never be forfeited. Subsequently, Washington himself benefitted from the “forcible ejection of the Indian tribes south of Ohio river” (to the tune of 45000 acres!).

Although it came at the cost of the indigenous tribes, the North American colonisation greatly benefited the poor and the desperate in the English Isles. Many indentured servants, who came to America to work in British property, were given land ownership after completing a term of service (as the land was in plenty and unclaimed). Thus, North America provided a certain route to social mobility for the English poor. Ferguson notes that three-fourth of all European migrants to British America during the colonial period were indentured servants.

In South America on the contrary, the poor did not benefit from colonisation.The loot from the silver mines in Peru and elsewhere that were plundered, went back to Spain, and was consolidated with the imperial authority. The Crown owned all the land. The labor was provided by the expropriated local tribes who were subdued by superior weapons and exotic diseases (smallpox, measles, influenza, and typhus to name a few). There was no question of property ownership or democratic governance. Ferguson says that this inexperience with democratic governance prevented the development of sustainable democratic institutions in South America when the Spanish imperial rulers ultimately retreated.

Thus, while democracy flourished in North America and ultimately led to the formation of the United States of America, South America reeled under autocrats and military tyrants.

4) The Fourth Front: Consumerism as the operating principle of the economy- Divergence from the Soviet model

One of the key differences between the Soviet model of development and its Western counterpart is that in the former, the central planners decided what subjects need to consume and produce, whereas in the Western model, consumers can choose from what is made available to them. Consumers apparently exercise their free-will to choose what they want ( albeit only in an eerie “matrix-esque” manner where the consumers believe that they are playing out their choice, while choice itself is determined by what is made available, and what is made “desirable” by a host of advertisement campaigns).

Ferguson says that it is this consumerism and industrialisation based on mass-production catering to the consumerist population that made the Western economy outsmart the Soviet model over a period of time.

To put this argument in perspective, the growth of the Soviet Union after the revolution until World War II was one of the fastest of any economy’s growth trajectory. Immediately after the October Revolution, in one of his writings, Lenin proclaimed that the “electrification” of the Soviet Union will be one of his top priorities. This disclosed the pitiful state of the Soviets in those times. However, in just five to six decades, the same nation would catapult the first spacecraft to orbit the earth. This was a tremendous symbolic feat, as the resources and the scientific sophistication needed to achieve such an act in the pre-computer era was just stupendous. The Soviet Union’s mastery of nuclear energy and missile technology occurred concurrently. This was in addition to the almost impossible feat of stalling the progress and reversing the fortunes of the formidable Nazi Germany in WWII. What the Western world achieved over centuries of imperialist hegemony, the Soviets achieved in barely four or five decades (nations like India and Brazil are still struggling with the technological feat that the Soviets achieved 70 years ago when computing technology was still at its infancy). This economic growth was the most important propaganda point that the communist bloc scored, well before the newly independent Third World nations like India were even born. Nations like India followed the Soviet example in planned development after being impressed by this spectacular growth trajectory.

A similar growth trajectory was achieved in Germany during the Nazi era (what is termed as the “rearmament period” after the World War I defeat). It is also said that the world, which was plunging through the 1930 Great Depression, was salvaged from the economic slowdown by WWII. The common denominator that links the growth of the Soviets, Nazi Germany and the reversal of the Great Depression is the command-style economy, following orders in a top-down model. Both in the Soviet Union and in Nazi Germany, this involved enormous human losses. It is estimated that in the Soviet Union, about ten million perished during Stalin’s regime, succumbing either to the firing squads or to the weather in the Siberian labor camps.

However, such command-style economies began faltering when the immediacy of a situation like a war or a calamity ceased to exist – which was what happened to the Soviet Union of the 1970s-1990s. The Soviet model of economy did not produce good quality consumer items, as people didn’t have any choice on what they wanted to consume. This led to continuously deteriorating standards, eventually leading to an economy that could not run on its own strengths.

Ferguson says that the differential that operated between the Soviet and the West was the design of the economy – one based on a top-down command system and the other based on an industry that relied on consumer choices and “mass consumption behavior”.

5) The Fifth Front: Protestant Work Ethics

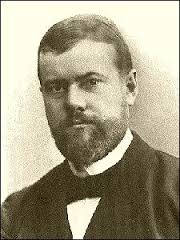

Ferguson advances German sociologist Max Weber’s theory that the emergence of North America as the leader of the Western world was because of the predominant presence of Anglo-Saxon Protestant Christian ethos.

To follow this idea, one needs to delve into the history of the Protestant movement in Europe.

Protestant “reformation” developed in Germany in the 16th century as a reaction to the bureaucratisation and commercialisation of the Roman Catholic Church. Martin Luther started the movement after feeling despondent about the indulgent money-making by the Church – to renovate Bishops’ Houses among many other things – in exchange for selling “penance” from what was called the “Treasury of Penance” (a treasury of accumulated “holiness credits” that Christian holy men from Jesus Christ onwards had aggregated by virtue of their corporal sacrifices). The Church had monopolised biblical services, and only the clergy were allowed to read the scriptures. Martin Luther revolted against this and rejected the idea of exchange of penances as well as the idea of requiring the mediation of the clergy for rendering the scriptures. His movement advocated literacy and encouraged the Lutherans to read the Bible themselves.

According to Protestant theology, Man was doomed, and only a select few will be “elected” by God for salvation. Work was regarded as a form of service to God, and devotion to it was considered as a means to escape the damnation that was due. Certain Protestant disciplines, like the Calvinists, sanctioned taking “interest on money saved” as legitimate (an act considered sinful in early Christianity). They also denounced beggary and discouraged giving alms (for abjuring work was considered sinful). Indeed, the Calvinist idea of sin, was that all human beings are born sinners by default – and until each and everyone tries to proactively take care to reduce the “sin credits”, all are doomed to hell. One of the ways to mitigate the sin-default was to immerse oneself in his work.

Weber’s thesis was that this devotion to work (as Godly service), the religious consent for lending money for interest and denouncement of living for sustenance, created an ethos that was congenial for the growth of industry (for dedicated labor was in plenty, and efficient enough) and capitalism ( for money was freely available for an interest). Money-making was not considered a sin, and indeed was a reflection of one’s devotion to work (ergo to God).

It is assumed that initial religious ethos soon translated to secular cultural ethos which characterises the work ethics of the West. However, Ferguson falters here onwards in arguing that this ethos is the manifestation of “religious belief”.

It is important to understand that the Protestant ideology per se did not aid capitalistic work ethics, but did it as a consequence. There are three issues:

a) Spread of literacy – the primary intention was for everyone to read the Bible and be “one’s own clergy”, but which by consequence (or as collateral effect) allowed people to learn many things besides the Bible.

b) Spread of printing press – primarily to disseminate Protestant literature, but which also had the collateral effect of disseminating other kinds of literature.

c) Devotion to work ( work as devotion) – this wasn’t a “primary” diktat in Protestant belief, but as the consequence of the diktat that God chooses only a select few, the majority are “damned”, and that the external sign of this damnation is misery and depravity. Therefore, to prevent the external sign of damnation becoming certain, most people devoted themselves to work to become successful. Subsequently, this work ethic became a part of the culture, as much as an etiquette, without whose observance people were not socially recognised.

Max Weber contrasted this with Hindu culture, where begging and alms-giving is a socially acceptable behaviour. The caste system assigned people who are involved in jobs involving contact with soil and metal as the “lower” castes. They were disallowed exposure to higher language skills and formal education. Vedic education itself was based on phonetic transmission. As innovation in technology developed amongst those who used tools, people were incapable of articulating innovations in a formal language. Technical innovations and the science based on it was largely limited, as a monopoly of individual families distributed their “intuitive” knowledge only amongst themselves. As most of the development in science and technology was developed by multiple people improvising – at different times and at different places – on the existing core of knowledge, the absence of an effective “online” social knowledge base that was freely accessible to everyone, hampered scientific and technological progress.

Because of the “online” nature of Europe and the United States ( owing to literacy and more importantly a media (printing press) to spread that), the innovations in one part of Europe would rapidly spread to another part and to the US, with back-to-back replication and improvisation (remember this was an era before patenting). The development of the steam locomotive in rapid succession, in England, Germany, the US and Belgium is a case in point. This would not have happened if not for the “online” nature of these societies. India, by contrast, was socially and culturally “offline”. The pan-Indian identity of the country was largely established by Hindu philosophical traditions, which were essentially “offline” to the large majority of Indian people. Most native scientific and technological innovations remained “offline” without the scope for “simultaneous replication or sequential improvisation”. Here, the advantage of having a large population (and possibly a large diversity of talents) was offset by the compartmentalisation and cultural segregation of society.

Atrocities- a point of Universal Convergence

If the above listed are the points of divergence between the West and the Rest, there is one issue in which the West and the rest converge in equal measure.

To give full credit, Ferguson, even while eulogising the West on every front, is very objective in listing the atrocities the West committed in building its Empires and its civilisation – a list which can easily rival that of any other nation or civilisation.

Ferguson explores the central theme of the Western ascent without too much emphasis on its righteousness ( albeit not entirely, as we shall see later). The rights and wrongs of modernity or even postmodernity were simply nonexistent in the eras preceding it. To write a historical treatise without acknowledging this, is a fatal error, which authors (especially history textbook writers) commit repeatedly. They do it for a variety of reasons, not least of which is based on a political agenda, of making one’s ideological position and historical icon more righteous than everyone else’s.

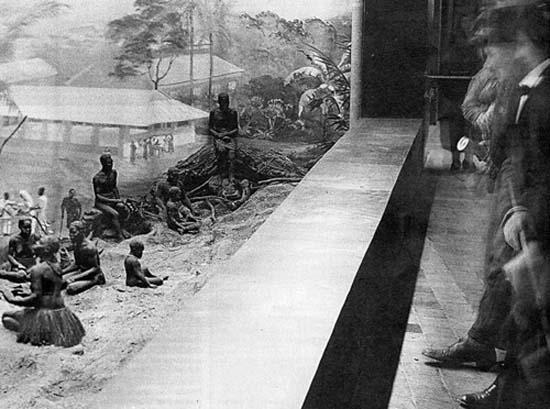

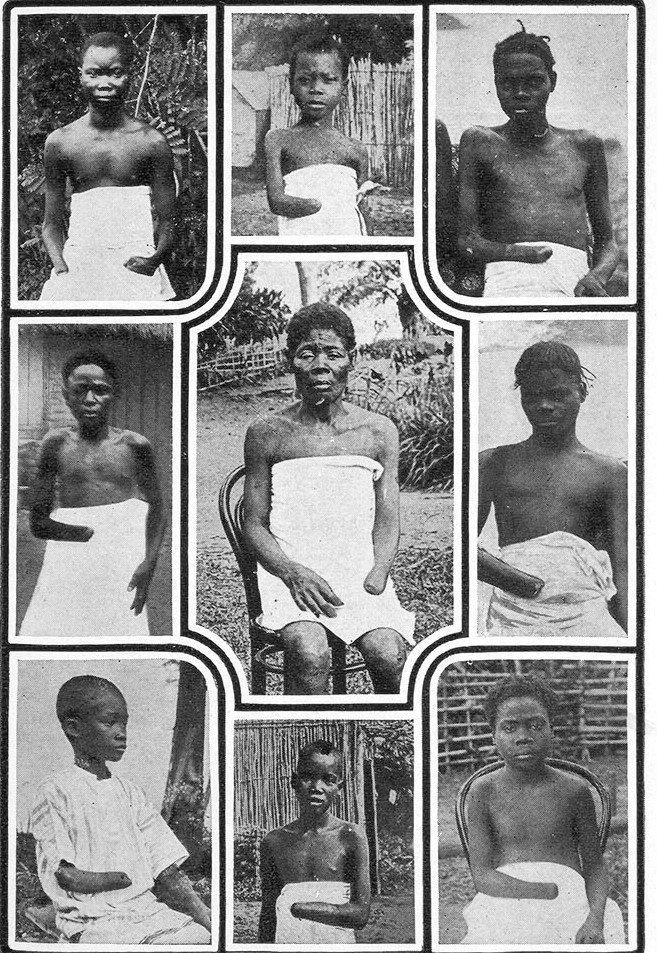

The colonisation of Africa in the 1800s by various European powers – commonly and rather ignobly called “scramble for Africa’”- illustrates the central theme of all history, including that of Western colonisation. While Ferguson briefly mentions this, he avoids painting a detailed picture of its true horrors. One of the chief patrons of the “scramble for Africa” was the Belgian king, Leopold-II. He coaxed all European powers interested in Africa to attend a meeting in Berlin in 1884 and “formalise the “partitioning” of Africa.

In the Berlin conference, Leopold managed to lay claim to a free Congo state, as a private dominion, in the guise of abolishing slavery and “civilising” natives. Leopold developed an organisation called ‘International African Society’ to advance this supposedly “humanitarian” goal. But once the Congo Free State was formed, Leopold’s real motives were revealed. He engaged in a tyranny of forced labor to collect ivory and rubber from Congo. He used women and children as captives to make men collect goods for his business. Those who protested were tortured. He engaged a private militia to flush out and liquidate protesters who ran into forests. As the orders to the private militia were to carry out their tasks as economically as possible, they had to collect the severed hands of killed rebels to tally against the bullets spent. As these terms could not be met all the time, the militia found it easy to sever the hands of women and children as proof of their successful operation. It is estimated that about one-fifth of the Congolese population perished in the whole episode. The situation was so outrageous, that even colonial apologists like Winston Churchill made statements against Leopold’s regime.

While Leopold acted as the most outrageous character of the Western scramble for Africa, the Trans-Atlantic slave trade does not find mention in the narratives of Western ascent. The discovery of the Americas necessitated a demand for an enormous amount of labor for the new world colonies. While indentured servants and native Americans were made to run the initial settlements, they soon proved insufficient ( while many indentured white servants got freedom at the end of their term, the native tribes started to decimate after contracting the exotic diseases brought by the colonists). Africa was then discovered as a source of cheap labor.

And not to take away the discredit, Africa, was indeed, the source of slaves for the Arabs who had “discovered” Africa before the Europeans. Following in the tradition of the Arab pioneers, the European slave traders would station along one of the coasts in Africa, and trade slaves from the African local rulers, who were keen on supplying their prisoners (whether prisoners of war or criminals) for a price. As this became a lucrative business, African rulers found “wars” to be a good business proposition. Soon, slave trade became the reason rather than the consequence for African internecine wars. It is further argued that many of the present day seemingly intractable hostilities among African nations/tribes seems to have their origin in conflicts incidental to the “raids” meant to procure subjects for the European slave trade – a situation quite similar to hostilities that exist between India and Pakistan and that exists between Arabs and Israelites, where a vicious cycle of deceit and violence make sure the hostilities never end, and none can decipher the origin of the “sin”.

It is said that the total casualty in the transatlantic slave trade was about 10 million, of which six million died in Africa itself, either in the hand of African slave raiders or the European enslavers. The mortality rate during the transatlantic slave shipment was around 15%. The conditions were so sordid and inhumane -even by the standards of 19th century Africa – that many slaves died by suicide, starving themselves or jumping into the sea. It was a routine affair to force-feed them to prevent them from killing themselves by starvation. Further, more died during the “seasoning” process where the enslavers equipped them to the rigours of American slavery.

This definitely was one of the worst holocausts the world had seen. In comparison, the number of jews who died in the Nazi Holocaust was about six million. The number of people who died in the Stalin-era in the Soviet Union were – according to “liberal”-western estimates – about ten million. The number of people who died in the Soviet Union during World War II was 27 million (more than a third of the total WWII casualties). Chengiz Khan’s massacres amounted to 40 million, and Timur’s contribution amounted to about 17 million.

Ferguson does not comment about the contribution of the African slave trade to the ascent of the West (or rather its masthead, the United States) or whether Western intervention in Africa amounts to a holocaust akin to the Nazi Holocaust of the 20th century. This is important, as from the middle of the 20th century, the key “patron” of the Western world has been the United States. In fact, one of the key differentials that shifted World War II from the Axis powers to the Allied powers was the entry of the United States to the war. Indeed, the once undisputed Britons were quite keen on the US entering the scenario to tilt the balance. Ever since WWII, it was the US, not the British or the French who acted as a counterweight to the Soviets. This was precisely because of the fact that the US was in a very healthy state vis-a-vis the UK or France, towards the middle of the 20th century. How much did the initial kick of cheap slave labour help this ascent of the behemoth that is America vis-a-vis other imperial regimes? This is clearly a point where we see that it was the New World that was the greatest beneficiary of the African slave trade.

However, Ferguson does not address this question. Instead he discusses the “Scramble for Africa” under the title of “Medicine” as one of the five differentials that mediated the ascent of the West. At one point Ferguson mentions that the Western colonisation of Africa helped Africa by improving its medical indices, including its life expectancy (p. 191 ). However, he neatly keeps this reference wrapped in a 46-page narrative of European atrocities in Africa. Throughout the survey the reader keeps wondering why Ferguson’s chapter on “Medicine” is but an essay on the Western conquest of Africa. Is he implying that the advances of western medicine in containing African diseases from malaria to yellow fever, mitigated European atrocities in Africa?

The author’s prejudices unravel when he talks about Marx, “an odious individual, an unkempt scrounger and a savage polemicist, who had an atrocious handwriting, and who depended on Engels, for whom socialism was an evening hobby, along with fox-hunting and womanising” or Stalin, “whose liquidation of the Kulaks – the landowning farmer class – was a euphemism for genocide” and the American students’ campus revolt against the US war in Vietnam, whose true aims were the “unlimited male access to female dormitories”. He also makes inaccurate conclusions based on inaccurate observations to fit his theory ( e.g. Kerala’s literacy being high due to the predominance of the Anglican Protestant Christians).

One wonders whether Ferguson would employ such techniques of hitting below the belt while reviewing his admirers, like the British thinker John Locke or any of the founding fathers of the United states.

The Rivals ( the Ascent of the Japan and China)

Ferguson makes interesting observations on the ascent of Japan and on the recent ascent of China.

The Japanese were so awed by the Western ascent that in the 1800s, they started to tour the West so as to decipher what has made the West so powerful. “Was it their political system? Their educational institution? Their culture? Or the way they dressed?” Unsure, they copied everything. Japan’s institutions were refashioned on Western models . The Japanese army uniform, their army drills, their education system, their business models, everything was “made as” it was in the West. Japanese swarmed western universities and returned to replicate and ultimately outrank the West in their own games.

The post-Deng Xiaoping China is also doing pretty much the same. The Chinese do business with African despots and oligarchs without any questions asked about corruption or human right abuses. Exactly the way the European colonists, and in the later years the United states, used to ally with any kind of tyrants to advance their economic and military goals. They swarm Western universities and plow back western study designs just the way the Japanese did half a century ago. For those who disparaged them as an assembly line of Western designer products, they responded by displaying indigenous technology to catapult space crafts to the moon. They accumulate US dollar reserves and treasury bonds to hedge any US “concern” of civil rights and human rights violation!

Truly, China is rising to become a “Chimerica” ( an economic marriage of convenience between China and America, in Ferguson’s own dictionary of neologisms).

In the book Niall Ferguson makes very pertinent observations on the rise of the West, and the nature of the superiority of its institutions. However, he does, many a time, succumb to amending facts in order to fit his theory.

Just as any other historian venturing to write an ideologically inspired interpretation of history, he overlooks many hiccoughs in his own narrative by hitting below the belt, especially when it comes to people whose ideology he detests. On the contrary, he treats his ideologues differently, being as “objective” as possible. Nonetheless, Ferguson’s book is a must-read course book for any one interested in the rise of the West, and the demise of the Rest. It is also a must-read for anyone trying to refashion the West among the Rest – for the West is not just few intersections in the map of the world, but truly a set of institutions and behaviours, whose replication alone will recreate its marvels

Hits: 4690